The migrant prison of Pagani near Mitilini, Lesvos stood at the centre of the activities of last year’s noborder. During the noborder, the refugees imprisoned in Pagani started hunger strikes, while noborders stages actions outside, which together led to a significant number of people being set free immediately. September saw numerous revolts inside Pagani, cells were set on fire and the police ultimately withdrew. Pagani was declared as officially closed at the beginning of October.

Since then, there have been differing reports about the current state of Pagani. Some said, it was still being used to accomodate refugees for a few days, before they were sent on towards Chios and Athens, and it was also uncertain whether Pagani still constituted a closed prison or a rather open reception centre.

So yesterday, we went to have a closer look at the facility in the industrial area of Mitilini. There, where last year hundreds of people were detained, we found a building void of any people, inmates and guardians alike. Searching for traces, we could not determine when the building was last used to accomodate people. Only one cell was accessible, inside, we found rows of beds complete with used mattrasses and old blankets, seemingly awaiting the arrival of new-comers. This supports the idea that Pagani is still occassionally used to house refugees. The other cells appeared similarily, while they were not so tidy and pre-arranged. The containers were totally empty.

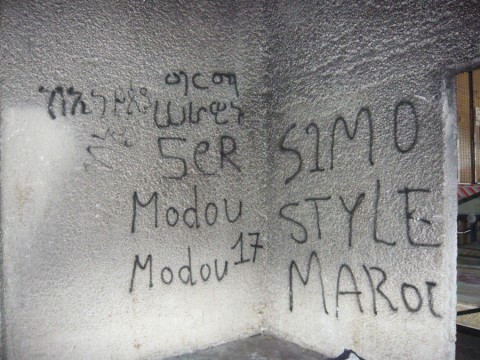

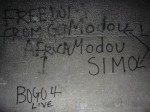

Pagani appeared like a ruin, less in the actual state of the building which is still as rotten as it was last year, but more in the sense of an archeologist: there were plenty of traces that pointed to how the building was used, and what the people that were imprisoned inside felt and did. The walls still carried writings in many languages, many were still darkened by the fires of the revolts. Pagani is the ruin of a system of the past.

Of course, there is technically nothing to prevent the local authorities to start using Pagani as a prison again. The whole setup, bars, gates, locks, beds, cells, is still there. But since the exposure of Pagani in 2009 as a place of humiliation and violation of human dignity, it is politically impossible for this to happen. Likewise, the euro-greek migration regime is on a course of modernisation. The old system, which was one of ignorance, irresponsibility and utter violence, has not only damaged the image of Greece in the world, it has also plunged the european internal migration system, namely the Dublin II regime, in a severe crisis. Both the new Greek government as well as the European Union have a profound interest in installing a new system of migration control in the Aegean. This includes elements like a perfunctory human rights compatible system of detention, but also the establishment of an efficient chain of deportation as well as the continued externalisation of migration control towards the borders of Turkey and Iran, Iraq and Syria. The Greek state has just presented its National Action Plan on the Management of Migration Flows to the European Commission. We will update you on these political developments soon.